"Nikesh Patel described it as the result of putting Severance and PhoneShop in a blender."

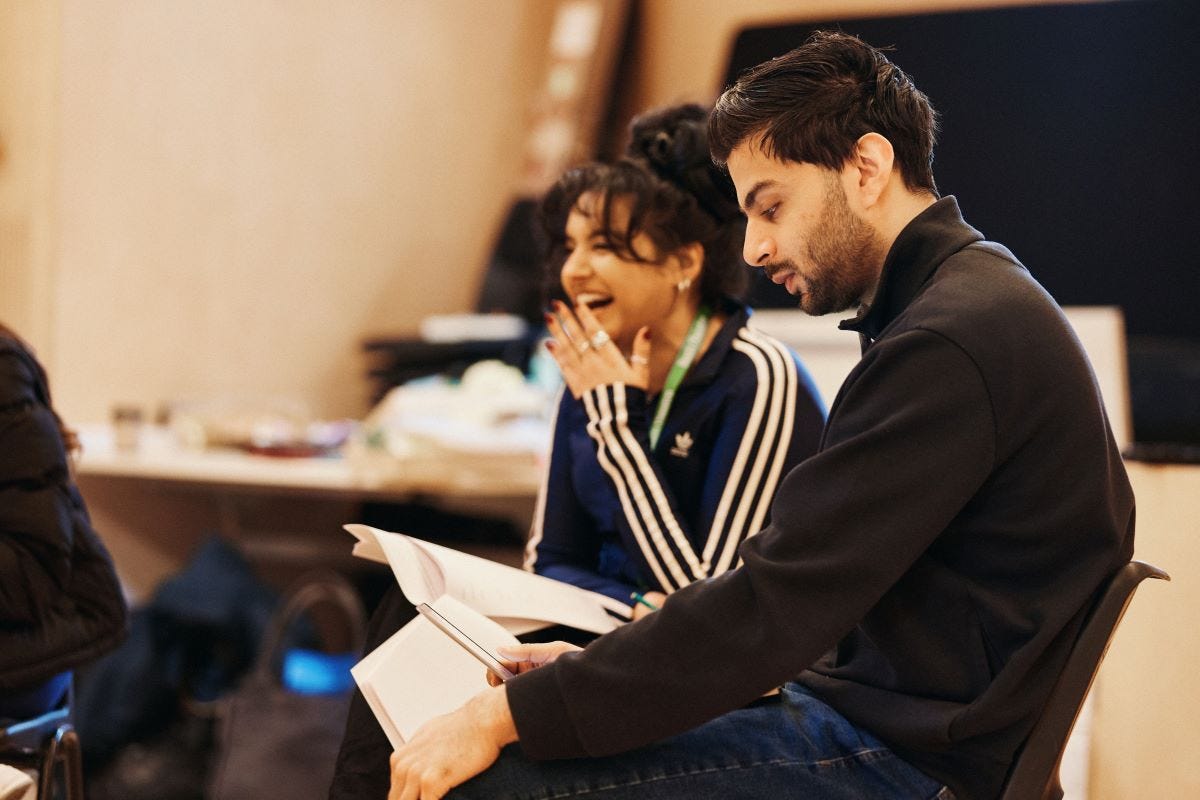

Director Milli Bhatia on her production of Mohamed-Zain Dada's Speed at the Bush Theatre. Plus: three shows to see next week.

Hello, and welcome to The Crush Bar, a newsletter about theatre by Fergus Morgan.

This is the free Friday issue, which usually contains an interview with an exciting theatremaker or an essay on a theatre-related topic. This week, it is a chat with director Milli Bhatia, whose staging of Mohamed-Zain Dada’s play Speed opened at the Bush Theatre last night. After that, there are your usual recommendations.

In case you missed it, here is this week’s issue of Shouts And Murmurs, which is a weekly round-up of the most interesting writing about theatre elsewhere…

You can get Shouts And Murmurs straight in your inbox every Tuesday - and help keep this newsletter going - by signing up as a paid supporter of The Crush Bar.

Theatres, companies, agencies and other organisations can now also sign-up as champion supporters of The Crush Bar, which gets their name in a dedicated tab on The Crush Bar’s Substack homepage and in the footer of every Friday issue.

Director Milli Bhatia has earned a reputation for staging thrilling productions of bold new plays.

There was Jasmine Lee-Jones’ seven methods of killing kylie jenner, a cacophonous social-media-storm of a drama about online activism, cultural appropriation and Black female identity that premiered Upstairs at the Royal Court Theatre in 2019, then transferred downstairs in 2021. There was Sonali Bhattacharyya’s Chasing Hares, a kaleidoscopic play about workers’ rights that hopped from contemporary London to 2000s Kolkata, which ran at the Young Vic in 2022. There was Bhattacharyya’s King Troll (The Fawn), a dystopian thriller about two sisters fleeing an oppressive regime, which premiered at the New Diorama Theatre last year. These shows - plus the immersive experience she co-created with Nina Segal and Ingrid Marvin in 2019, the script-in-hand performances of Lucy Kirkwood’s Maryland she co-directed in 2021, and more - have made Bhatia one of the most exciting young directors around.

The daughter of actor Meera Syal, Bhatia discovered a love for directing as a teenager, trained at Birkbeck after studying at UEA, spent two years as an associate artist at the Bush Theatre, then joined the Royal Court Theatre in 2018. She spent the following seven years with the organisation under artistic director Vicky Featherstone, first as a trainee director, then as literary associate, then as an associate artist. She left the Royal Court Theatre late last year and now works as a freelance director. Her next job: Mohamed-Zain Dada’s new play Speed, which opened at the Bush Theatre last night.

You worked with the playwright Mohamed-Zain Dada before on Blue Mist at the Royal Court Theatre in 2023. When did you two first meet?

We actually first met ten years ago here at the Bush Theatre, under Madani Younis. I was working as an associate artist. He was working in the community department. Madani introduced us and said we would get on, and we did. We made Blue Mist together, which was his debut play. We have made a short film together, which is coming out soon. And now, ten years later, we are back at the Bush Theatre making Speed together. It feels like a really rare, really special collaboration. He is an artist of real integrity, artistry and bravery, and our politics and ambition in terms of the stories we want to tell align.

Blue Mist was about three young Muslim men hanging out in a shisha lounge, chatting about their lives. What happens in Speed?

Nikesh Patel, who is in our cast, described it as the result of putting Severance and Phone Shop in a blender. The setting is a speed awareness course that is a pilot scheme run by the DVLA, trialling a combination of speed awareness and road rage management. The entire cast is deliberately entirely South Asian, which brings up lots of big questions around British stoicism, around the codeswitching of the South Asian diaspora, and about who has the right to be angry in this country.

I’m ashamed to say I have done two speed awareness courses. They are very odd environments. You suddenly feel like you are back at school. Have you done one?

I haven’t, actually. What really excited me about the play was this idea of suddenly putting adults into this structured teaching environment, where they are meeting each other for the first time. It brings up all these questions about how we choose to present ourselves and how much control we have over that.

What has inspired your staging?

We have had some really interesting conversations in the room. We have also been really inspired by a photographer called Hark1karan and his book Zimmers Of Southall, which is basically about South Asian communities and their cars. We were also really inspired by Jasleen Kaur’s exhibition Alter Altar, at the centre of which was this amazing red car covered in a lace doily. It won the Turner Prize. Zain and I went to see it together. I remember my grandparents telling stories about the pride of buying their first car in this country. They are real symbols for the South Asian community. It has been a real joy to dig into some of the art exploring that.

Critics praised Blue Mist for the energy and wit of its dialogue. How does Speed compare?

It is a very different play to Blue Mist. Zain has such an extraordinary knack for dialogue and he writes South Asian characters with such care and humour. That is one of the many things I love about his work. Blue Mist had that and so does this.

Your mum is the actor Meera Syal and your stepdad is the actor Sanjeev Bhaskar. Were you always going to be involved in performance somehow?

I was always encouraged to be a storyteller. I was surrounded by them. I never knew my dad’s parents but my mum’s parents were very artistic people. They really encouraged both my mum and her brother and me and my brother to be creative. I feel very lucky to have grown up in a house where culture was celebrated.

What were your theatrical influences growing up?

I grew up in Leytonstone in East London, so I was loyally taken to the panto at Theatre Royal Stratford East every year. I still go. I went to see Pinocchio last year.

The piece of theatre that really changed my perspective, though, was Nirbhaya by Yael Farber. It was about the Delhi rape of 2012 and it was created with real victims of domestic and sexual violence from India. I saw it at the Edinburgh Fringe when I was 18 and my mouth was open for the entire hour. It was so theatrical and delicate and brave, but it was also a piece of political action. I fiercely believed in why it needed to be told. It hugely inspired me to be a director. I still think about it now.

How did you become a director?

I always knew I wanted to be a storyteller, but I didn’t know how. I did a lot of music and acting as a kid. There was always a bit of me that felt acting wasn’t for me, though. I went to the University of East Anglia and did a degree in English and Drama, still not knowing what I wanted to do. Then I discovered directing.

After graduating from UEA, I went to Birkbeck to do an MFA in Theatre Directing, because I was so sure that I wanted to be a director. One of my first ever jobs after that was assisting Lynette Linton on a play called Assata Taught Me by Kalungi Ssbandeke at the Gate Theatre. I then did a part-time development programme at the Bush Theatre called Project 2036, which is when I met Mohamed-Zain Dada.

By that point, I had made up my mind that I was going to keep applying for the trainee director job at the Royal Court until I got it. The first time, I didn’t get it. The second time, I did. I was a trainee there for two years, then I worked in the literary department, then Vicky Featherstone asked me to become an associate.

You must have a real affection for The Royal Court.

I do. The Royal Court is where I saw so much work that really inspired me. I have a lot of affection for Vicky, too, because she really championed me. I was incredibly young when I joined and she saw potential in me that I couldn’t even see in myself. I owe a lot to her, and to Madani Younis, who gave me my first professional show when I was at the Bush. I think they both did incredible jobs at those theatres.

Do you like your productions to have a political impetus of some kind?

That’s a great question. I am very intentional. Whenever I come across a play, I think about what it wants to say to an audience and whether I am the right person to direct it. Often, there is luck involved there. I feel so lucky to have got the chance to direct seven methods of killing kylie jenner, for example, which was an extraordinary piece of work, both in form and politics. With every writer I work with, we have shared an intentionality and clarity. Why this play? Why us?

You have worked with Mohamed-Zain Dada before. You have worked with Sonali Bhattacharyya a lot, too. How important are those relationships with writers?

So important. I’ve been incredibly lucky with the people that I’ve managed to cultivate artistic relationships with. Every time Zain or Sonali ask me to direct one of their plays, it feels like a huge honour to be trusted with their work.

I’ve noticed that you only seem to direct new plays. Why is that?

Well, I did an adaptation of Macbeth last year, but, yes, I love working with new writers. I guess it is because I really grew up as a director at the Royal Court, and I love the liveness of working with a playwright. That can’t happen with existing plays. And, to be honest, people don’t approach me to direct them.

Would you like to direct a classic play?

I would love to. I would love to do an Arthur Miller or a Tennessee Williams. I’d really love to do a Lorca. Hopefully, I will get the chance one day.

As someone who has built a career directing bold new plays, do you worry about theatre becoming risk-averse due to the financial struggles the industry is facing?

I do absolutely worry about that outside of new writing theatres like the Royal Court and the Bush, which are so brilliant at what they do. New plays need nurturing and time. What I worry about most, though, when it comes to limited resources, is access for both audiences and artists. There are real barriers to entering and working in this industry. The pay is bad. The lifestyle is precarious. The opportunities are few. Speaking as a middle-class person, I would love our industry to be less middle-class, but those barriers are in the way.

What does the future hold for you after Speed?

Mohamed-Zain Dada and I have a short film coming out. We are in post-production at the moment. It is called Auntie Ji and it is a really beautiful story that we shot in Shepherd’s Bush. We are really excited about it. And Sonali Bhattacharyya and I are developing a horror play we made together last year at the New Diorama Theatre called King Troll (The Fawn) into a feature film.

My first love will always be theatre, and I hope I will always be lucky enough to keep making it, but I am really excited by cinema, too. I’m particularly interested in horror. Horror influences everything I do. I like how it can work as a social metaphor and that is something Sonali absolutely aced with King Troll (The Fawn). It is a horror about the home office. It is an incredible story to tell through that lens.

Is there anyone you really want to work with? Or buildings you want to work in?

Well, the list of writers I want to work with is huge and I would love to direct some classic plays. To be honest, though, if I can sustain a career directing stories I really care about, which are about people I want to make space for, I’ll be happy.

Speed is at the Bush Theatre until May 17.

Three shows to see next week

MTFestUK 2025 - The Other Palace, until April 17

The Other Palace’s annual festival of new musicals returned is back: four new shows, presented in workshop form over a fortnight at the Victoria venue. Charli Eglinton’s Love Can and Mahlon Prince’s More have been and gone, but there is still time to catch Theatre Mum by Rory Svensson and Helen Greenham and Nerds by Hal Goldberg, Jordan Allen-Dutton and Erik Weiner. You can get tickets via the button below.

Learning To Fly/Piece Of Work - Theatre Royal Stratford East, until April 16

Storyteller James Rowland has been a fixture of fringe theatre since bursting onto the scene with Team Viking nine years ago. Since then, he has earned acclaim with a series of gentle, moving shows, including A Hundred Different Words For Love, Revelations, and James Rowland Dies At The End Of The Show. He is currently on tour and arrives at Theatre Royal Stratford East on Wednesday for his biggest gig ever with a double-bill of Learning To Fly and Piece Of Work. You can get tickets via the button below.

Ghosts - Lyric Hammersmith, until May 10

This modern-day adaptation of Ibsen’s classic play about a family torn apart by secrets reunites writer Gary Owen and director Rachel O’Riordan, who previously collaborated on the acclaimed plays Iphigenia In Splott, Romeo and Julie and Killology. It stars It’s A Sin’s Callum Scott Howells, Rivals’ Victoria Smurfit and Sex Education’s Patricia Allison, plus Rhashan Stone and Deka Walmsley. You can read my interview with Allison in The Stage here and get tickets via the button below.

Thanks for reading and supporting The Crush Bar

Thanks to all 4027 subscribers, to all 121 paid supporters, and particularly to The Crush Bar’s champion supporters, whose contributions make all this possible.

The Royal Court Theatre, Ellie Keel Productions, The Women’s Prize For Playwriting, Francesca Moody Productions, Raw Material Arts, Jermyn Street Theatre; Hampstead Theatre.

Your organisation can become a champion supporter of The Crush Bar, join that list, and help keep its independent coverage of theatre going via the button below.

That is it for this week. If you want to get in touch about anything raised in this issue - or anything at all - just reply to this newsletter, or email me at fergusmorgan@hotmail.co.uk, or you can find me on Bluesky.

Fergus

Thanks so much for the shout out Fergus. Appreciate it