"The British Museum really pissed me off. That anger became the motivation behind this play."

Singaporean theatremaker Joel Tan on his new play about repatriating artifacts, which opens at the Royal Court Theatre next week. Plus: three shows to see.

Hello, and welcome to The Crush Bar, a newsletter about theatre by Fergus Morgan.

This is the free Friday issue, which usually contains an interview with an exciting theatremaker or an essay on a theatre-related topic. This week, it is a chat with playwright Joel Tan, whose new play Scenes From A Repatriation starts performances at the Royal Court Theatre next week. After that, there are your usual recommendations.

In case you missed it, here is this week’s issue of Shouts And Murmurs, which is a weekly round-up of the most interesting writing about theatre elsewhere…

You can get Shouts And Murmurs straight in your inbox every Tuesday - and help keep this newsletter going - by signing up as a paid supporter of The Crush Bar.

Theatres, companies, agencies and other organisations can now also sign-up as champion supporters of The Crush Bar, which gets their name in a dedicated tab on The Crush Bar’s Substack homepage and in the footer of every Friday issue.

Singaporean playwright Joel Tan is not afraid of tackling tricky topics.

His play No Particular Order, which was staged at Theatre503 in 2021, depicted the rise and fall of a fascist state through scenes in the lives of ordinary people. His 2022 play God Is A Woman, which was staged by Singaporean theatre company Wild Rice in 2023, satirised the city-state’s censorious attitude to the arts. And his new play, Scenes From A Repatriation, which starts performances Upstairs at the Royal Court Theatre next week, is a kaleidoscopic examination of the issues around repatriating artifacts.

Born and raised in Singapore, Tan studied English at the National University of Singapore, then spent the first seven years of his career there. In 2017, he moved to London to study playwriting at Drama Centre London, then developed his practice via a residency scheme run by Theatre503 and the Royal Court Writer’s Group. He has split his time between the two cities ever since, working as an artist-in-residence and literary manager with Wild Rice and as a creative associate at Singapore’s Centre42.

Scenes From A Repatriation is your debut at the Royal Court. What is it about?

It surrounds this 1000-year-old statue of the bodhisattva Guanyin, who is regarded in various East Asian and South-East Asian cultures as a goddess of mercy, although they are not necessarily female. It emerges through the course of the play that this statue has a murky provenance. When this comes to light, it results in a hefty repatriation claim from China that creates a whole bunch of conflict.

That’s the broad narrative, but the play zooms in on various personal encounters that a range of characters have with the statue, from staff to visitors. The play is an attempt to look at the big issue of the restitution of art from multiple gazes.

Is it based on a real artifact?

The statue is fictional and the gesture of the piece is mostly fictional, but the nugget of it is from my very real personal aggravation at the British Museum when I visited for the first time in 2017. I was walking around and I became very sensitive to the politics of display in the museum. There were some specific Chinese Buddhist artifacts that were displayed in a really callous manner, and that really pissed me off. I guess that flash of anger became the motivation to write this play.

People will be familiar with the discourse around the Parthenon Marbles and the Benin Bronzes. Why did you decide to base your play on a fictional Chinese artifact?

For me, there was something interesting about the imaginative leap of wondering what would happen if there was an object that was stolen from China. How would China being the geopolitical force that it is today affect those conversations?

Why was it important to incorporate a wide range of perspectives into the play?

When I started looking deeper into these questions of looting and restitution, and into the very traumatic and violent histories that surround these objects, I began to realise that there is never just one way of looking at a particular artifact. There is an art history perspective, of course. There is a curatorial perspective. There is an intergovernmental perspective. There’s also the perspective of the community that might have housed that artifact. I also think there is a spiritual layer at work.

Artifacts are haunted by their pasts. I felt intuitively that a play that addressed all those perspectives needed to have multiple lenses. These artifacts are looked at by so many different people on a daily basis and every one of those people has a different relationship with it. I wanted the play to hold as much of that as possible.

Does the play make any particular argument over the repatriation of artifacts?

I don’t think the play makes a very strong rhetorical case for how museums should act in all repatriation cases. It is just examining the questions that surround all that. It is not easy to tap into that spiritual layer of these conversations in the press or on social media, but theatre has the unique potential to tease it out.

Scenes From A Repatriation is directed by Emma Clark and PJ Stanley - AKA Emma + PJ - whose work is beautiful and interesting and layered. What will it look like?

We are still piecing it together so I’m not sure, but I think there is going to be something quite lush and operative about the visual language of this production. That really excites me. It is a studio play but it deals with some really big ideas, and I think this production will be able to hold those big messy questions.

Is having two directors instead of one difficult?

Ordinarily, I would say yes, but it is not with Emma + PJ. They work so well together. They have a kind of telepathy. This has been a really enjoyable process.

How much does it mean to have your play produced at the Royal Court?

It’s thrilling. Ever since I started writing plays, I’ve admired this building. It has such a huge legacy. It feels quite intimidating to be here. It is heart-warming that this building is championing this play, too, though. This play, fundamentally, is quite global in its gesture. It feels like the Royal Court has always had an openness to plays from other parts of the world, and it is nice to be part of that heritage.

When did you start writing plays?

I did an English degree at the National University of Singapore. I wanted to do creative writing, but the only course on offer was a class called Introduction to Playwriting, which was led by this wonderful Malaysian playwright called Huzir Sulaiman. That was the first time I had even thought about theatre. I discovered that I really enjoyed the form, that I really enjoy the musicality of writing dialogue and the act of imagining characters and creating images on stage. It just rocketed from there. Huzir sent my first play on to Wild Rice, which is a theatre company in Singapore, and they gave it a staging at Singapore Theatre Festival in 2011.

What is the theatre industry in Singapore like?

Singapore has a really robust theatre scene that has been active for a very long time. In the 1950s and 1960s, then again in the 1990s, it had a very strong experimental, underground bent. In the past twenty years, it has got quite professional. We have big theatres. We have new writing companies. We have companies that do all sorts of work. It is a small scene, but an intense and loving and supportive one. Everybody knows everybody and there is a lot of pride in the work that we do. It is also very political. I think it is currently poised at quite a critical tangent to the status quo of political and social life in the country.

I have read that there is a degree of censorship in Singaporean theatre. Is that true?

The Singapore government is very autocratic. Some would say authoritarian. For a long time, there has been a deep culture of censorship across many aspects of life in Singapore, but especially in the arts. All public performances have to be licensed. You have to submit your script to a government agency called the Infocomm Media Development Authority, which I find a very ironic name.

What are you not allowed to write about?

The boundaries are unclear. It used to be that you could not directly criticise the government, although now there seems to be a bit more leeway with that. Race and religion are no-go areas. They are big issues in Singapore because it is a multi-racial, multi-religious society and the government sees itself as a custodian of inter-community relations. Any kind of queer content would get flagged, too.

It is not that you can’t write about these things exactly. It is more that they get assigned different ratings depending on how problematic they are found to be. That then restricts the people that come and see it and that has a trickle-down effect on sales. At the most extreme end, there is stuff that just does not get on because it is too objectionable. That tends to be stuff that questions orthodox narratives about history or makes direct references to political personages.

Does that make it hard to be a playwright in Singapore?

It isn’t hard, but it is unpredictable. You never know when you might trip the wire. I often wonder whether that is by design. I wonder whether we are kept suspended in a state of ambiguity on purpose. Then you wonder if you have internalised censorship as a result. You wonder if you unconsciously make choices that lead you down the path of least resistance. You wonder if you are making the bravest, hardest-hitting, most important work that you can. That is a niggling feeling.

You wrote about this in your play G*D Is A Woman. Tell me about that.

G*D Is A Woman was a satirical play that looked deeply into Singapore’s culture of censorship in the arts. It satirised the way ministers and politicians think about these issues. It had a strong critique of conservative Christianity, too, which is a major force in Singapore. There have been a lot of cases of conservative religious people writing into government agencies to complain about works of art. The Catholic Church got upset by some slutty nuns dancing on stage at a Madonna concert, for example, and I think she had to cut that number from her show.

When did you move to London?

I moved to London in 2017 to do a masters in dramatic writing at Drama Centre London, which doesn’t exist any more. I moved back to Singapore during the pandemic. Now I split my time between both cities. I’ve been making work in Singapore since 2011, when I had my first play put on professionally. The bulk of my practice is there, where I am an artist-in-residence with Wild Rice. It is only recently that I started having my work produced here. I had a play called No Particular Order produced at Theatre503 in 2021.

How has your playwriting changed since you started working in London?

Before moving here, I wrote almost exclusively about Singapore. I knew that audience really well. Here, I didn’t know what audiences wanted or what work I wanted to put on. That challenged me to start thinking a lot more internationally, both in terms of the stories I want to tell, but also in terms of the conversations I want my work to sit at the intersection of. That is scary but also rewarding.

What does the future hold for you after Scenes From A Repatriation?

The dream is to work evenly between the UK and Singapore. I love Singapore very much, even though I have harsh things to say about it, and I am very invested in the project of pushing the boundaries of what is possible and articulable there. I also love making work here, though, because of how expansive my ambition can be.

At the moment, I’m interested in writing a play about the left and how eats itself from the inside out. I want to write about the way an identitarian politics has led, in some cases, to a paralysing of the left. I want to dramatize that thorny situation.

You seem like a playwright that is keen to dive into thorny topics?

I think that is because I come from Singapore. Theatre there is very brash and direct. Perhaps because we are told ‘no’ all the time, we just go: ‘Okay, I’m just going to say it and see what happens.’ I enjoy that directness of approach.

Scenes From A Repatriation is at the Royal Court Theatre until May 24.

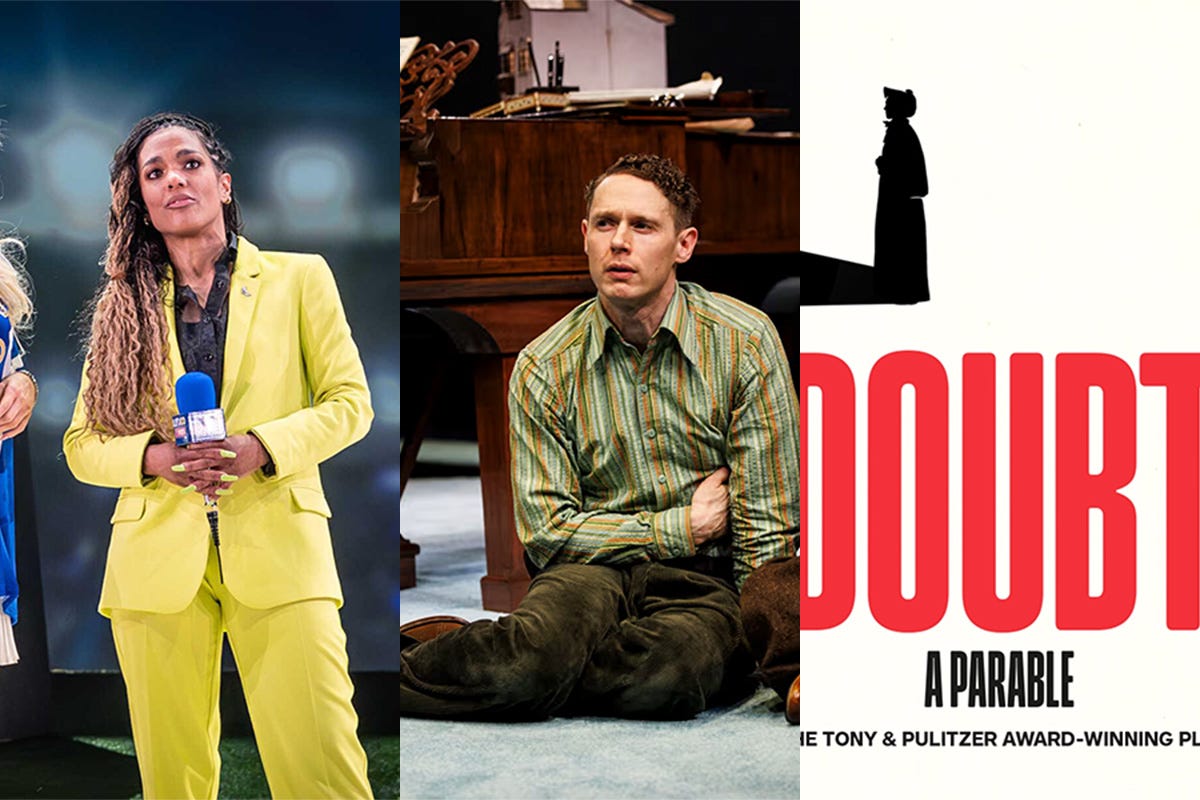

Three shows to see next week

Much Ado About Nothing - Royal Shakespeare Company, until May 24

Mike Longhurst’s new Stratford-upon-Avon staging of Shakespeare’s sparkling comedy is set in the world of elite football. Nick Blood’s Benedick is the star player of Messina FC, who have just triumphed in the Champions League. Freema Agyeman’s Beatrice is a football pundit, who delights in giving him a grilling. You can read my interview with Agyeman in The Stage here, and get tickets via the button below.

Ben and Imo - Orange Tree Theatre, until May 17

Set in a stormy Aldeburgh in 1952, Mark Ravenhill’s two-hander focuses on the intimate relationship between composer Benjamin Britten, played by Samuel Barnett, and his musical assistant Imogen Holst, played by Victoria Yeates. It premiered in Stratford-upon-Avon last year and now transfers to the Orange Tree Theatre. You can read my interview with Yeates in The Stage here and get tickets via the button below.

Doubt: A Parable - Dundee Rep, until May 10

This is a big year for Dundee Rep. In July, James Graham’s new play Make It Happen, starring Brian Cox, will preview at the theatre before opening at the Edinburgh International Festival. Before that, though, director Joanna Bowman, who delivered a sensational staging of Caryl Churchill’s Escaped Alone at the Tron Theatre last year, revives John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about secrecy and scandal in an American Catholic school. You can get tickets via the button below.

Thanks for reading and supporting The Crush Bar

Thanks to all 4163 subscribers, to all 126 paid supporters, and particularly to The Crush Bar’s champion supporters, whose contributions make all this possible.

The Royal Court Theatre, Ellie Keel Productions, The Women’s Prize For Playwriting, Francesca Moody Productions, Raw Material Arts, Jermyn Street Theatre; Hampstead Theatre.

Your organisation can become a champion supporter of The Crush Bar, join that list, and help keep its independent coverage of theatre going via the button below.

That is it for this week. If you want to get in touch about anything raised in this issue - or anything at all - just reply to this newsletter, or email me at fergusmorgan@hotmail.co.uk, or you can find me on Bluesky.

Fergus